|

A Discrete-Event Network Simulator

|

Models |

This chapter describes the TCP models available in ns-3.

ns-3 was written to support multiple TCP implementations. The implementations inherit from a few common header classes in the src/network directory, so that user code can swap out implementations with minimal changes to the scripts.

There are two important abstract base classes:

There are presently three implementations of TCP available for ns-3.

It should also be mentioned that various ways of combining virtual machines with ns-3 makes available also some additional TCP implementations, but those are out of scope for this chapter.

In brief, the native ns-3 TCP model supports a full bidirectional TCP with connection setup and close logic. Several congestion control algorithms are supported, with NewReno the default, and Westwood, Hybla, and HighSpeed also supported. Multipath-TCP and TCP Selective Acknowledgements (SACK) are not yet supported in the ns-3 releases.

Until the ns-3.10 release, ns-3 contained a port of the TCP model from GTNetS. This implementation was substantially rewritten by Adriam Tam for ns-3.10. In 2015, the TCP module has been redesigned in order to create a better environment for creating and carrying out automated tests. One of the main changes involves congestion control algorithms, and how they are implemented.

Before ns-3.25 release, a congestion control was considered as a stand-alone TCP through an inheritance relation: each congestion control (e.g. TcpNewReno) was a subclass of TcpSocketBase, reimplementing some inherited methods. The architecture was redone to avoid this inheritance, the fundamental principle of the GSoC proposal was avoiding this inheritance, by making each congestion control a separate class, and making an interface to exchange important data between TcpSocketBase and the congestion modules. For instance, similar modularity is used in Linux.

Along with congestion control, Fast Retransmit and Fast Recovery algorithms have been modified; in previous releases, these algorithms were demanded to TcpSocketBase subclasses. Starting from ns-3.25, they have been merged inside TcpSocketBase. In future releases, they can be extracted as separate modules, following the congestion control design.

In many cases, usage of TCP is set at the application layer by telling the ns-3 application which kind of socket factory to use.

Using the helper functions defined in src/applications/helper and src/network/helper, here is how one would create a TCP receiver:

// Create a packet sink on the star "hub" to receive these packets

uint16_t port = 50000;

Address sinkLocalAddress(InetSocketAddress (Ipv4Address::GetAny (), port));

PacketSinkHelper sinkHelper ("ns3::TcpSocketFactory", sinkLocalAddress);

ApplicationContainer sinkApp = sinkHelper.Install (serverNode);

sinkApp.Start (Seconds (1.0));

sinkApp.Stop (Seconds (10.0));

Similarly, the below snippet configures OnOffApplication traffic source to use TCP:

// Create the OnOff applications to send TCP to the server

OnOffHelper clientHelper ("ns3::TcpSocketFactory", Address ());

The careful reader will note above that we have specified the TypeId of an abstract base class TcpSocketFactory. How does the script tell ns-3 that it wants the native ns-3 TCP vs. some other one? Well, when internet stacks are added to the node, the default TCP implementation that is aggregated to the node is the ns-3 TCP. This can be overridden as we show below when using Network Simulation Cradle. So, by default, when using the ns-3 helper API, the TCP that is aggregated to nodes with an Internet stack is the native ns-3 TCP.

To configure behavior of TCP, a number of parameters are exported through the ns-3 attribute system. These are documented in the Doxygen <http://www.nsnam.org/doxygen/classns3_1_1_tcp_socket.html> for class TcpSocket. For example, the maximum segment size is a settable attribute.

To set the default socket type before any internet stack-related objects are created, one may put the following statement at the top of the simulation program:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpL4Protocol::SocketType", StringValue ("ns3::TcpNewReno"));

For users who wish to have a pointer to the actual socket (so that socket operations like Bind(), setting socket options, etc. can be done on a per-socket basis), Tcp sockets can be created by using the Socket::CreateSocket() method. The TypeId passed to CreateSocket() must be of type ns3::SocketFactory, so configuring the underlying socket type must be done by twiddling the attribute associated with the underlying TcpL4Protocol object. The easiest way to get at this would be through the attribute configuration system. In the below example, the Node container “n0n1” is accessed to get the zeroth element, and a socket is created on this node:

// Create and bind the socket...

TypeId tid = TypeId::LookupByName ("ns3::TcpNewReno");

Config::Set ("/NodeList/*/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType", TypeIdValue (tid));

Ptr<Socket> localSocket =

Socket::CreateSocket (n0n1.Get (0), TcpSocketFactory::GetTypeId ());

Above, the “*” wild card for node number is passed to the attribute configuration system, so that all future sockets on all nodes are set to NewReno, not just on node ‘n0n1.Get (0)’. If one wants to limit it to just the specified node, one would have to do something like:

// Create and bind the socket...

TypeId tid = TypeId::LookupByName ("ns3::TcpNewReno");

std::stringstream nodeId;

nodeId << n0n1.Get (0)->GetId ();

std::string specificNode = "/NodeList/" + nodeId.str () + "/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType";

Config::Set (specificNode, TypeIdValue (tid));

Ptr<Socket> localSocket =

Socket::CreateSocket (n0n1.Get (0), TcpSocketFactory::GetTypeId ());

Once a TCP socket is created, one will want to follow conventional socket logic and either connect() and send() (for a TCP client) or bind(), listen(), and accept() (for a TCP server). Please note that applications usually create the sockets they use automatically, and so is not straightforward to connect direcly to them using pointers. Please refer to the source code of your preferred application to discover how and when it creates the socket.

In the following there is an analysis on the public interface of the TCP socket, and how it can be used to interact with the socket itself. An analysis of the callback fired by the socket is also carried out. Please note that, for the sake of clarity, we will use the terminology “Sender” and “Receiver” to clearly divide the functionality of the socket. However, in TCP these two roles can be applied at the same time (i.e. a socket could be a sender and a receiver at the same time): our distinction does not lose generality, since the following definition can be applied to both sockets in case of full-duplex mode.

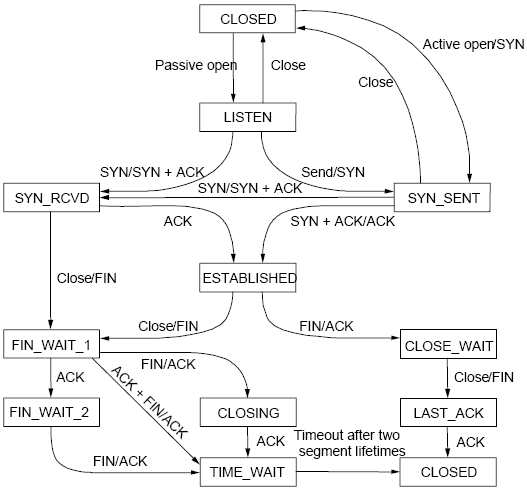

TCP state machine (for commodity use)

TCP State machine

In ns-3 we are fully compliant with the state machine depicted in Figure TCP State machine.

Public interface for receivers (e.g. servers receiving data)

Public interface for senders (e.g. clients uploading data)

Public callbacks

These callbacks are called by the TCP socket to notify the application of interesting events. We will refer to these with the protected name used in socket.h, but we will provide the API function to set the pointers to these callback as well.

Here follows a list of supported TCP congestion control algorithms. For an academic peer-reviewed paper on these congestion control algorithms, see http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518 .

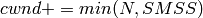

New Reno algorithm introduces partial ACKs inside the well-established Reno algorithm. This and other modifications are described in RFC 6582. We have two possible congestion window increment strategy: slow start and congestion avoidance. Taken from RFC 5681:

During slow start, a TCP increments cwnd by at most SMSS bytes for each ACK received that cumulatively acknowledges new data. Slow start ends when cwnd exceeds ssthresh (or, optionally, when it reaches it, as noted above) or when congestion is observed. While traditionally TCP implementations have increased cwnd by precisely SMSS bytes upon receipt of an ACK covering new data, we RECOMMEND that TCP implementations increase cwnd, per Equation (1), where N is the number of previously unacknowledged bytes acknowledged in the incoming ACK.

(1)

During congestion avoidance, cwnd is incremented by roughly 1 full-sized segment per round-trip time (RTT), and for each congestion event, the slow start threshold is halved.

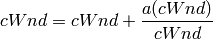

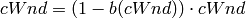

TCP HighSpeed is designed for high-capacity channels or, in general, for TCP connections with large congestion windows. Conceptually, with respect to the standard TCP, HighSpeed makes the cWnd grow faster during the probing phases and accelerates the cWnd recovery from losses. This behavior is executed only when the window grows beyond a certain threshold, which allows TCP Highspeed to be friendly with standard TCP in environments with heavy congestion, without introducing new dangers of congestion collapse.

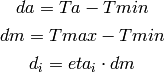

Mathematically:

The function a() is calculated using a fixed RTT the value 100 ms (the lookup table for this function is taken from RFC 3649). For each congestion event, the slow start threshold is decreased by a value that depends on the size of the slow start threshold itself. Then, the congestion window is set to such value.

The lookup table for the function b() is taken from the same RFC. More informations at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518

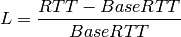

The key idea behind TCP Hybla is to obtain for long RTT connections the same instantaneous transmission rate of a reference TCP connection with lower RTT. With analytical steps, it is shown that this goal can be achieved by modifying the time scale, in order for the throughput to be independent from the RTT. This independence is obtained through the use of a coefficient rho.

This coefficient is used to calculate both the slow start threshold and the congestion window when in slow start and in congestion avoidance, respectively.

More informations at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518

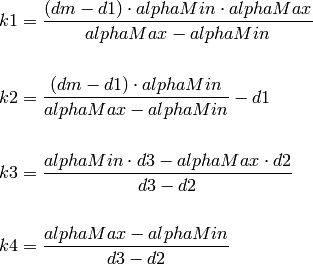

Westwood and Westwood+ employ the AIAD (Additive Increase/Adaptive Decrease)· congestion control paradigm. When a congestion episode happens,· instead of halving the cwnd, these protocols try to estimate the network’s bandwidth and use the estimated value to adjust the cwnd.· While Westwood performs the bandwidth sampling every ACK reception,· Westwood+ samples the bandwidth every RTT.

More informations at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=381704 and http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2512757

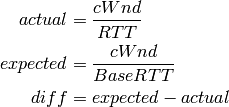

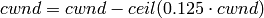

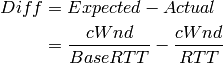

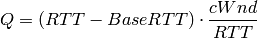

TCP Vegas is a pure delay-based congestion control algorithm implementing a proactive scheme that tries to prevent packet drops by maintaining a small backlog at the bottleneck queue. Vegas continuously samples the RTT and computes the actual throughput a connection achieves using Equation (1) and compares it with the expected throughput calculated in Equation (2). The difference between these 2 sending rates in Equation (3) reflects the amount of extra packets being queued at the bottleneck.

To avoid congestion, Vegas linearly increases/decreases its congestion window to ensure the diff value fall between the two predefined thresholds, alpha and beta. diff and another threshold, gamma, are used to determine when Vegas should change from its slow-start mode to linear increase/decrease mode. Following the implementation of Vegas in Linux, we use 2, 4, and 1 as the default values of alpha, beta, and gamma, respectively, but they can be modified through the Attribute system.

More informations at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/49.464716

Scalable improves TCP performance to better utilize the available bandwidth of a highspeed wide area network by altering NewReno congestion window adjustment algorithm. When congestion has not been detected, for each ACK received in an RTT, Scalable increases its cwnd per:

Following Linux implementation of Scalable, we use 50 instead of 100 to account for delayed ACK.

On the first detection of congestion in a given RTT, cwnd is reduced based on the following equation:

More informations at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=956989

TCP Veno enhances Reno algorithm for more effectively dealing with random packet loss in wireless access networks by employing Vegas’s method in estimating the backlog at the bottleneck queue to distinguish between congestive and non-congestive states.

The backlog (the number of packets accumulated at the bottleneck queue) is calculated using Equation (1):

where:

Veno makes decision on cwnd modification based on the calculated N and its predefined threshold beta.

Specifically, it refines the additive increase algorithm of Reno so that the connection can stay longer in the stable state by incrementing cwnd by 1/cwnd for every other new ACK received after the available bandwidth has been fully utilized, i.e. when N exceeds beta. Otherwise, Veno increases its cwnd by 1/cwnd upon every new ACK receipt as in Reno.

In the multiplicative decrease algorithm, when Veno is in the non-congestive state, i.e. when N is less than beta, Veno decrements its cwnd by only 1/5 because the loss encountered is more likely a corruption-based loss than a congestion-based. Only when N is greater than beta, Veno halves its sending rate as in Reno.

More informations at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2002.807336

In TCP Bic the congestion control problem is viewed as a search problem. Taking as a starting point the current window value and as a target point the last maximum window value (i.e. the cWnd value just before the loss event) a binary search technique can be used to update the cWnd value at the midpoint between the two, directly or using an additive increase strategy if the distance from the current window is too large.

This way, assuming a no-loss period, the congestion window logarithmically approaches the maximum value of cWnd until the difference between it and cWnd falls below a preset threshold. After reaching such a value (or the maximum window is unknown, i.e. the binary search does not start at all) the algorithm switches to probing the new maximum window with a ‘slow start’ strategy.

If a loss occur in either these phases, the current window (before the loss) can be treated as the new maximum, and the reduced (with a multiplicative decrease factor Beta) window size can be used as the new minimum.

More informations at: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=1354672

YeAH-TCP (Yet Another HighSpeed TCP) is a heuristic designed to balance various requirements of a state-of-the-art congestion control algorithm:

YeAH operates between 2 modes: Fast and Slow mode. In the Fast mode when the queue occupancy is small and the network congestion level is low, YeAH increments its congestion window according to the aggressive STCP rule. When the number of packets in the queue grows beyond a threshold and the network congestion level is high, YeAH enters its Slow mode, acting as Reno with a decongestion algorithm. YeAH employs Vegas’ mechanism for calculating the backlog as in Equation (2). The estimation of the network congestion level is shown in Equation (3).

(2)

(3)

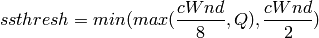

To ensure TCP friendliness, YeAH also implements an algorithm to detect the presence of legacy Reno flows. Upon the receipt of 3 duplicate ACKs, YeAH decreases its slow start threshold according to Equation (3) if it’s not competing with Reno flows. Otherwise, the ssthresh is halved as in Reno:

More information: http://www.csc.lsu.edu/~sjpark/cs7601/4-YeAH_TCP.pdf

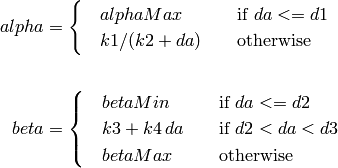

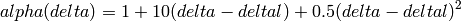

TCP Illinois is a hybrid congestion control algorithm designed for high-speed networks. Illinois implements a Concave-AIMD (or C-AIMD) algorithm that uses packet loss as the primary congestion signal to determine the direction of window update and queueing delay as the secondary congestion signal to determine the amount of change.

The additive increase and multiplicative decrease factors (denoted as alpha and beta, respectively) are functions of the current average queueing delay da as shown in Equations (1) and (2). To improve the protocol robustness against sudden fluctuations in its delay sampling, Illinois allows the increment of alpha to alphaMax only if da stays below d1 for a some (theta) amount of time.

where the calculations of k1, k2, k3, and k4 are shown in the following:

Other parameters include da (the current average queueing delay), and Ta (the average RTT, calculated as sumRtt / cntRtt in the implementation) and Tmin (baseRtt in the implementation) which is the minimum RTT ever seen. dm is the maximum (average) queueing delay, and Tmax (maxRtt in the implementation) is the maximum RTT ever seen.

Illinois only executes its adaptation of alpha and beta when cwnd exceeds a threshold called winThresh. Otherwise, it sets alpha and beta to the base values of 1 and 0.5, respectively.

Following the implementation of Illinois in the Linux kernel, we use the following default parameter settings:

More information: http://www.doi.org/10.1145/1190095.1190166

H-TCP has been designed for high BDP (Bandwidth-Delay Product) paths. It is a dual mode protocol. In normal conditions, it works like traditional TCP with the same rate of increment and decrement for the congestion window. However, in high BDP networks, when it finds no congestion on the path after deltal seconds, it increases the window size based on the alpha function in the following:

where deltal is a threshold in seconds for switching between the modes and delta is the elapsed time from the last congestion. During congestion, it reduces the window size by multiplying by beta function provided in the reference paper. The calculated throughput between the last two consecutive congestion events is considered for beta calculation.

The transport TcpHtcp can be selected in the program examples/tcp/tcp-variants/comparison to perform an experiment with H-TCP, although it is useful to increase the bandwidth in this example (e.g. to 20 Mb/s) to create a higher BDP link, such as

./waf --run "tcp-variants-comparison --transport_prot=TcpHtcp --bandwidth=20Mbps --duration=10"

More information (paper): http://www.hamilton.ie/net/htcp3.pdf

More information (Internet Draft): https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-leith-tcp-htcp-06

The following tests are found in the src/internet/test directory. In general, TCP tests inherit from a class called TcpGeneralTest, which provides common operations to set up test scenarios involving TCP objects. For more information on how to write new tests, see the section below on Writing TCP tests.

Several tests have dependencies outside of the internet module, so they are located in a system test directory called src/test/ns3tcp. Three of these six tests involve use of the Network Simulation Cradle, and are disabled if NSC is not enabled in the build.

Several TCP validation test results can also be found in the wiki page describing this implementation.

Writing (or porting) a congestion control algorithms from scratch (or from other systems) is a process completely separated from the internals of TcpSocketBase.

All operations that are delegated to a congestion control are contained in the class TcpCongestionOps. It mimics the structure tcp_congestion_ops of Linux, and the following operations are defined:

virtual std::string GetName () const;

virtual uint32_t GetSsThresh (Ptr<const TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t bytesInFlight);

virtual void IncreaseWindow (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t segmentsAcked);

virtual void PktsAcked (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t segmentsAcked,const Time& rtt);

virtual Ptr<TcpCongestionOps> Fork ();

The most interesting methods to write are GetSsThresh and IncreaseWindow. The latter is called when TcpSocketBase decides that it is time to increase the congestion window. Much information is available in the Transmission Control Block, and the method should increase cWnd and/or ssThresh based on the number of segments acked.

GetSsThresh is called whenever the socket needs an updated value of the slow start threshold. This happens after a loss; congestion control algorithms are then asked to lower such value, and to return it.

PktsAcked is used in case the algorithm needs timing information (such as RTT), and it is called each time an ACK is received.

The TCP subsystem supports automated test cases on both socket functions and congestion control algorithms. To show how to write tests for TCP, here we explain the process of creating a test case that reproduces a bug (#1571 in the project bug tracker).

The bug concerns the zero window situation, which happens when the receiver can not handle more data. In this case, it advertises a zero window, which causes the sender to pause transmission and wait for the receiver to increase the window.

The sender has a timer to periodically check the receiver’s window: however, in modern TCP implementations, when the receiver has freed a “significant” amount of data, the receiver itself sends an “active” window update, meaning that the transmission could be resumed. Nevertheless, the sender timer is still necessary because window updates can be lost.

Note

During the text, we will assume some knowledge about the general design of the TCP test infrastructure, which is explained in detail into the Doxygen documentation. As a brief summary, the strategy is to have a class that sets up a TCP connection, and that calls protected members of itself. In this way, subclasses can implement the necessary members, which will be called by the main TcpGeneralTest class when events occour. For example, after processing an ACK, the method ProcessedAck will be invoked. Subclasses interested in checking some particular things which must have happened during an ACK processing, should implement the ProcessedAck method and check the interesting values inside the method. To get a list of available methods, please check the Doxygen documentation.

We describe the writing of two test case, covering both situations: the sender’s zero-window probing and the receiver “active” window update. Our focus will be on dealing with the reported problems, which are:

However, other things should be checked in the test:

To construct the test case, one first derives from the TcpGeneralTest class:

The code is the following:

TcpZeroWindowTest::TcpZeroWindowTest (const std::string &desc)

: TcpGeneralTest (desc)

{

}

Then, one should define the general parameters for the TCP connection, which will be one-sided (one node is acting as SENDER, while the other is acting as RECEIVER):

We have also to define the link properties, because the above definition does not work for every combination of propagation delay and sender application behavior.

To define the properties of the environment (e.g. properties which should be set before the object creation, such as propagation delay) one next implements ehe method ConfigureEnvironment:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::ConfigureEnvironment ()

{

TcpGeneralTest::ConfigureEnvironment ();

SetAppPktCount (20);

SetMTU (500);

SetTransmitStart (Seconds (2.0));

SetPropagationDelay (MilliSeconds (50));

}

For other properties, set after the object creation, one can use ConfigureProperties (). The difference is that some values, such as initial congestion window or initial slow start threshold, are applicable only to a single instance, not to every instance we have. Usually, methods that requires an id and a value are meant to be called inside ConfigureProperties (). Please see the doxygen documentation for an exhaustive list of the tunable properties.

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::ConfigureProperties ()

{

TcpGeneralTest::ConfigureProperties ();

SetInitialCwnd (SENDER, 10);

}

To see the default value for the experiment, please see the implementation of both methods inside TcpGeneralTest class.

Note

If some configuration parameters are missing, add a method called “SetSomeValue” which takes as input the value only (if it is meant to be called inside ConfigureEnvironment) or the socket and the value (if it is meant to be called inside ConfigureProperties).

To define a zero-window situation, we choose (by design) to initiate the connection with a 0-byte rx buffer. This implies that the RECEIVER, in its first SYN-ACK, advertises a zero window. This can be accomplished by implementing the method CreateReceiverSocket, setting an Rx buffer value of 0 bytes (at line 6 of the following code):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | Ptr<TcpSocketMsgBase>

TcpZeroWindowTest::CreateReceiverSocket (Ptr<Node> node)

{

Ptr<TcpSocketMsgBase> socket = TcpGeneralTest::CreateReceiverSocket (node);

socket->SetAttribute("RcvBufSize", UintegerValue (0));

Simulator::Schedule (Seconds (10.0),

&TcpZeroWindowTest::IncreaseBufSize, this);

return socket;

}

|

Even so, to check the active window update, we should schedule an increase of the buffer size. We do this at line 7 and 8, scheduling the function IncreaseBufSize.

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::IncreaseBufSize ()

{

SetRcvBufSize (RECEIVER, 2500);

}

Which utilizes the SetRcvBufSize method to edit the RxBuffer object of the RECEIVER. As said before, check the Doxygen documentation for class TcpGeneralTest to be aware of the various possibilities that it offers.

Note

By design, we choose to mantain a close relationship between TcpSocketBase and TcpGeneralTest: they are connected by a friendship relation. Since friendship is not passed through inheritance, if one discovers that one needs to access or to modify a private (or protected) member of TcpSocketBase, one can do so by adding a method in the class TcpGeneralSocket. An example of such method is SetRcvBufSize, which allows TcpGeneralSocket subclasses to forcefully set the RxBuffer size.

void

TcpGeneralTest::SetRcvBufSize (SocketWho who, uint32_t size)

{

if (who == SENDER)

{

m_senderSocket->SetRcvBufSize (size);

}

else if (who == RECEIVER)

{

m_receiverSocket->SetRcvBufSize (size);

}

else

{

NS_FATAL_ERROR ("Not defined");

}

}

Next, we can start to follow the TCP connection:

While the general structure is defined, and the connection is started, we need to define a way to check the rWnd field on the segments. To this aim, we can implement the methods Rx and Tx in the TcpGeneralTest subclass, checking each time the actions of the RECEIVER and the SENDER. These methods are defined in TcpGeneralTest, and they are attached to the Rx and Tx traces in the TcpSocketBase. One should write small tests for every detail that one wants to ensure during the connection (it will prevent the test from changing over the time, and it ensures that the behavior will stay consistent through releases). We start by ensuring that the first SYN-ACK has 0 as advertised window size:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::Tx(const Ptr<const Packet> p, const TcpHeader &h, SocketWho who)

{

...

else if (who == RECEIVER)

{

NS_LOG_INFO ("\tRECEIVER TX " << h << " size " << p->GetSize());

if (h.GetFlags () & TcpHeader::SYN)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetWindowSize(), 0,

"RECEIVER window size is not 0 in the SYN-ACK");

}

}

....

}

Pratically, we are checking that every SYN packet sent by the RECEIVER has the advertised window set to 0. The same thing is done also by checking, in the Rx method, that each SYN received by SENDER has the advertised window set to 0. Thanks to the log subsystem, we can print what is happening through messages. If we run the experiment, enabling the logging, we can see the following:

./waf shell

gdb --args ./build/utils/ns3-dev-test-runner-debug --test-name=tcp-zero-window-test --stop-on-failure --fullness=QUICK --assert-on-failure --verbose

(gdb) run

0.00s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Tx(): 0.00 SENDER TX 49153 > 4477 [SYN] Seq=0 Ack=0 Win=32768 ns3::TcpOptionWinScale(2) ns3::TcpOptionTS(0;0) size 36

0.05s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Rx(): 0.05 RECEIVER RX 49153 > 4477 [SYN] Seq=0 Ack=0 Win=32768 ns3::TcpOptionWinScale(2) ns3::TcpOptionTS(0;0) ns3::TcpOptionEnd(EOL) size 0

0.05s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Tx(): 0.05 RECEIVER TX 4477 > 49153 [SYN|ACK] Seq=0 Ack=1 Win=0 ns3::TcpOptionWinScale(0) ns3::TcpOptionTS(50;0) size 36

0.10s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Rx(): 0.10 SENDER RX 4477 > 49153 [SYN|ACK] Seq=0 Ack=1 Win=0 ns3::TcpOptionWinScale(0) ns3::TcpOptionTS(50;0) ns3::TcpOptionEnd(EOL) size 0

0.10s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Tx(): 0.10 SENDER TX 49153 > 4477 [ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=32768 ns3::TcpOptionTS(100;50) size 32

0.15s TcpZeroWindowTestSuite:Rx(): 0.15 RECEIVER RX 49153 > 4477 [ACK] Seq=1 Ack=1 Win=32768 ns3::TcpOptionTS(100;50) ns3::TcpOptionEnd(EOL) size 0

(...)

The output is cut to show the threeway handshake. As we can see from the headers, the rWnd of RECEIVER is set to 0, and thankfully our tests are not failing. Now we need to test for the persistent timer, which sould be started by the SENDER after it receives the SYN-ACK. Since the Rx method is called before any computation on the received packet, we should utilize another method, namely ProcessedAck, which is the method called after each processed ACK. In the following, we show how to check if the persistent event is running after the processing of the SYN-ACK:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::ProcessedAck (const Ptr<const TcpSocketState> tcb,

const TcpHeader& h, SocketWho who)

{

if (who == SENDER)

{

if (h.GetFlags () & TcpHeader::SYN)

{

EventId persistentEvent = GetPersistentEvent (SENDER);

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (persistentEvent.IsRunning (), true,

"Persistent event not started");

}

}

}

Since we programmed the increase of the buffer size after 10 simulated seconds, we expect the persistent timer to fire before any rWnd changes. When it fires, the SENDER should send a window probe, and the receiver should reply reporting again a zero window situation. At first, we investigates on what the sender sends:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | if (Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () <= 6.0)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (p->GetSize () - h.GetSerializedSize(), 0,

"Data packet sent anyway");

}

else if (Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () > 6.0 &&

Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () <= 7.0)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (m_zeroWindowProbe, false, "Sent another probe");

if (! m_zeroWindowProbe)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (p->GetSize () - h.GetSerializedSize(), 1,

"Data packet sent instead of window probe");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetSequenceNumber(), SequenceNumber32 (1),

"Data packet sent instead of window probe");

m_zeroWindowProbe = true;

}

}

|

We divide the events by simulated time. At line 1, we check everything that happens before the 6.0 seconds mark; for instance, that no data packets are sent, and that the state remains OPEN for both sender and receiver.

Since the persist timeout is initialized at 6 seconds (excercise left for the reader: edit the test, getting this value from the Attribute system), we need to check (line 6) between 6.0 and 7.0 simulated seconds that the probe is sent. Only one probe is allowed, and this is the reason for the check at line 11.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | if (Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () > 6.0 &&

Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () <= 7.0)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetSequenceNumber(), SequenceNumber32 (1),

"Data packet sent instead of window probe");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetWindowSize(), 0,

"No zero window advertised by RECEIVER");

}

|

For the RECEIVER, the interval between 6 and 7 seconds is when the zero-window segment is sent.

Other checks are redundant; the safest approach is to deny any other packet exchange between the 7 and 10 seconds mark.

else if (Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () > 7.0 &&

Simulator::Now ().GetSeconds () < 10.0)

{

NS_FATAL_ERROR ("No packets should be sent before the window update");

}

The state checks are performed at the end of the methods, since they are valid in every condition:

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (GetCongStateFrom (GetTcb(SENDER)), TcpSocketState::CA_OPEN,

"Sender State is not OPEN");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (GetCongStateFrom (GetTcb(RECEIVER)), TcpSocketState::CA_OPEN,

"Receiver State is not OPEN");

Now, the interesting part in the Tx method is to check that after the 10.0 seconds mark (when the RECEIVER sends the active window update) the value of the window should be greater than zero (and precisely, set to 2500):

else if (Simulator::Now().GetSeconds() >= 10.0)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetWindowSize(), 2500,

"Receiver window not updated");

}

To be sure that the sender receives the window update, we can use the Rx method:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | if (Simulator::Now().GetSeconds() >= 10.0)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetWindowSize(), 2500,

"Receiver window not updated");

m_windowUpdated = true;

}

|

We check every packet after the 10 seconds mark to see if it has the window updated. At line 5, we also set to true a boolean variable, to check that we effectively reach this test.

Last but not least, we implement also the NormalClose() method, to check that the connection ends with a success:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::NormalClose (SocketWho who)

{

if (who == SENDER)

{

m_senderFinished = true;

}

else if (who == RECEIVER)

{

m_receiverFinished = true;

}

}

The method is called only if all bytes are transmitted successfully. Then, in the method FinalChecks(), we check all variables, which should be true (which indicates that we have perfectly closed the connection).

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::FinalChecks ()

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (m_zeroWindowProbe, true,

"Zero window probe not sent");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (m_windowUpdated, true,

"Window has not updated during the connection");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (m_senderFinished, true,

"Connection not closed successfully (SENDER)");

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (m_receiverFinished, true,

"Connection not closed successfully (RECEIVER)");

}

To run the test, the usual way is

./test.py -s tcp-zero-window-test

PASS: TestSuite tcp-zero-window-test

1 of 1 tests passed (1 passed, 0 skipped, 0 failed, 0 crashed, 0 valgrind errors)

To see INFO messages, use a combination of ./waf shell and gdb (really useful):

./waf shell && gdb --args ./build/utils/ns3-dev-test-runner-debug --test-name=tcp-zero-window-test --stop-on-failure --fullness=QUICK --assert-on-failure --verbose

and then, hit “Run”.

Note

This code magically runs without any reported errors; however, in real cases, when you discover a bug you should expect the existing test to fail (this could indicate a well-written test and a bad-writted model, or a bad-written test; hopefull the first situation). Correcting bugs is an iterative process. For instance, commits created to make this test case running without errors are 11633:6b74df04cf44, (others to be merged).

The Network Simulation Cradle (NSC) is a framework for wrapping real-world network code into simulators, allowing simulation of real-world behavior at little extra cost. This work has been validated by comparing situations using a test network with the same situations in the simulator. To date, it has been shown that the NSC is able to produce extremely accurate results. NSC supports four real world stacks: FreeBSD, OpenBSD, lwIP and Linux. Emphasis has been placed on not changing any of the network stacks by hand. Not a single line of code has been changed in the network protocol implementations of any of the above four stacks. However, a custom C parser was built to programmatically change source code.

NSC has previously been ported to ns-2 and OMNeT++, and was was added to ns-3 in September 2008 (ns-3.2 release). This section describes the ns-3 port of NSC and how to use it.

To some extent, NSC has been superseded by the Linux kernel support within Direct Code Execution (DCE). However, NSC is still available through the bake build system. NSC supports Linux kernels 2.6.18 and 2.6.26, but newer versions of the kernel have not been ported.

Presently, NSC has been tested and shown to work on these platforms: Linux i386 and Linux x86-64. NSC does not support powerpc. Use on FreeBSD or OS X is unsupported (although it may be able to work).

Building NSC requires the packages flex and bison.

As of ns-3.17 or later, NSC must either be downloaded separately from its own repository, or downloading when using the bake build system of ns-3.

For ns-3.17 or later releases, when using bake, one must configure NSC as part of an “allinone” configuration, such as:

$ cd bake

$ python bake.py configure -e ns-allinone-3.19

$ python bake.py download

$ python bake.py build

Instead of a released version, one may use the ns-3 development version by specifying “ns-3-allinone” to the configure step above.

NSC may also be downloaded from its download site using Mercurial:

$ hg clone https://secure.wand.net.nz/mercurial/nsc

Prior to the ns-3.17 release, NSC was included in the allinone tarball and the released version did not need to be separately downloaded.

NSC may be built as part of the bake build process; alternatively, one may build NSC by itself using its build system; e.g.:

$ cd nsc-dev

$ python scons.py

Once NSC has been built either manually or through the bake system, change into the ns-3 source directory and try running the following configuration:

$ ./waf configure

If NSC has been previously built and found by waf, then you will see:

Network Simulation Cradle : enabled

If NSC has not been found, you will see:

Network Simulation Cradle : not enabled (NSC not found (see option --with-nsc))

In this case, you must pass the relative or absolute path to the NSC libraries with the “–with-nsc” configure option; e.g.

$ ./waf configure --with-nsc=/path/to/my/nsc/directory

For ns-3 releases prior to the ns-3.17 release, using the build.py script in ns-3-allinone directory, NSC will be built by default unless the platform does not support it. To explicitly disable it when building ns-3, type:

$ ./waf configure --enable-examples --enable-tests --disable-nsc

If waf detects NSC, then building ns-3 with NSC is performed the same way with waf as without it. Once ns-3 is built, try running the following test suite:

$ ./test.py -s ns3-tcp-interoperability

If NSC has been successfully built, the following test should show up in the results:

PASS TestSuite ns3-tcp-interoperability

This confirms that NSC is ready to use.

There are a few example files. Try:

$ ./waf --run tcp-nsc-zoo

$ ./waf --run tcp-nsc-lfn

These examples will deposit some .pcap files in your directory, which can be examined by tcpdump or wireshark.

Let’s look at the examples/tcp/tcp-nsc-zoo.cc file for some typical usage. How does it differ from using native ns-3 TCP? There is one main configuration line, when using NSC and the ns-3 helper API, that needs to be set:

InternetStackHelper internetStack;

internetStack.SetNscStack ("liblinux2.6.26.so");

// this switches nodes 0 and 1 to NSCs Linux 2.6.26 stack.

internetStack.Install (n.Get(0));

internetStack.Install (n.Get(1));

The key line is the SetNscStack. This tells the InternetStack helper to aggregate instances of NSC TCP instead of native ns-3 TCP to the remaining nodes. It is important that this function be called before calling the Install() function, as shown above.

Which stacks are available to use? Presently, the focus has been on Linux 2.6.18 and Linux 2.6.26 stacks for ns-3. To see which stacks were built, one can execute the following find command at the ns-3 top level directory:

$ find nsc -name "*.so" -type f

nsc/linux-2.6.18/liblinux2.6.18.so

nsc/linux-2.6.26/liblinux2.6.26.so

This tells us that we may either pass the library name liblinux2.6.18.so or liblinux2.6.26.so to the above configuration step.

NSC TCP shares the same configuration attributes that are common across TCP sockets, as described above and documented in Doxygen

Additionally, NSC TCP exports a lot of configuration variables into the ns-3 attributes system, via a sysctl-like interface. In the examples/tcp/tcp-nsc-zoo example, you can see the following configuration:

// this disables TCP SACK, wscale and timestamps on node 1 (the attributes

represent sysctl-values).

Config::Set ("/NodeList/1/$ns3::Ns3NscStack<linux2.6.26>/net.ipv4.tcp_sack",

StringValue ("0"));

Config::Set ("/NodeList/1/$ns3::Ns3NscStack<linux2.6.26>/net.ipv4.tcp_timestamps",

StringValue ("0"));

Config::Set ("/NodeList/1/$ns3::Ns3NscStack<linux2.6.26>/net.ipv4.tcp_window_scaling",

StringValue ("0"));

These additional configuration variables are not available to native ns-3 TCP.

Also note that default values for TCP attributes in ns-3 TCP may differ from the nsc TCP implementation. Specifically in ns-3:

- TCP default MSS is 536

- TCP Delayed Ack count is 2

Therefore when making comparisons between results obtained using nsc and ns-3 TCP, care must be taken to ensure these values are set appropriately. See /examples/tcp/tcp-nsc-comparision.cc for an example.

This subsection describes the API that NSC presents to ns-3 or any other simulator. NSC provides its API in the form of a number of classes that are defined in sim/sim_interface.h in the nsc directory.

The ns-3 implementation makes use of the above NSC API, and is implemented as follows.

The three main parts are:

src/internet/model/nsc-tcp-l4-protocol is the main class. Upon Initialization, it loads an nsc network stack to use (via dlopen()). Each instance of this class may use a different stack. The stack (=shared library) to use is set using the SetNscLibrary() method (at this time its called indirectly via the internet stack helper). The nsc stack is then set up accordingly (timers etc). The NscTcpL4Protocol::Receive() function hands the packet it receives (must be a complete tcp/ip packet) to the nsc stack for further processing. To be able to send packets, this class implements the nsc send_callback method. This method is called by nsc whenever the nsc stack wishes to send a packet out to the network. Its arguments are a raw buffer, containing a complete TCP/IP packet, and a length value. This method therefore has to convert the raw data to a Ptr<Packet> usable by ns-3. In order to avoid various ipv4 header issues, the nsc ip header is not included. Instead, the tcp header and the actual payload are put into the Ptr<Packet>, after this the Packet is passed down to layer 3 for sending the packet out (no further special treatment is needed in the send code path).

This class calls ns3::NscTcpSocketImpl both from the nsc wakeup() callback and from the Receive path (to ensure that possibly queued data is scheduled for sending).

src/internet/model/nsc-tcp-socket-impl implements the nsc socket interface. Each instance has its own nscTcpSocket. Data that is Send() will be handed to the nsc stack via m_nscTcpSocket->send_data(). (and not to nsc-tcp-l4, this is the major difference compared to ns-3 TCP). The class also queues up data that is Send() before the underlying descriptor has entered an ESTABLISHED state. This class is called from the nsc-tcp-l4 class, when the nsc-tcp-l4 wakeup() callback is invoked by nsc. nsc-tcp-socket-impl then checks the current connection state (SYN_SENT, ESTABLISHED, LISTEN...) and schedules appropriate callbacks as needed, e.g. a LISTEN socket will schedule Accept to see if a new connection must be accepted, an ESTABLISHED socket schedules any pending data for writing, schedule a read callback, etc.

Note that ns3::NscTcpSocketImpl does not interact with nsc-tcp directly: instead, data is redirected to nsc. nsc-tcp calls the nsc-tcp-sockets of a node when its wakeup callback is invoked by nsc.

For more information, see this wiki page.